Metra has changed the schedules for 10 of its 11 lines in the past three years alone.

Those schedule changes range from minor adjustments to reflect actual operating conditions or the addition of a station, all the way to more comprehensive redesigns to accommodate increased ridership demand in particular areas and the implementation of the Positive Train Control (PTC) safety system.

At Metra, schedule changes are the result of months of planning and analysis from its service design team and transportation managers. Each schedule redesign has some driving factor. That factor for two of the most recent schedules, on the BNSF and Rock Island lines, has been PTC.

The first step when redesigning a schedule is to make a chart that shows how each set of equipment is used throughout the day: where does it go and when and where does it flip (start a run in the opposite direction).

Once this has been charted out, the service design team determines where these flips do not meet the parameters that must be met in order to operate with PTC. Schedulers established that trains must have 12 minutes to flip terminal stations downtown and 15 minutes to flip at outlying stations. Once they know where the schedule doesn’t meet these parameters, they can focus on what parts of the schedule need to change.

Then come the other objectives to attract more riders and enhance service.

“For the Rock Island, for example, we wanted to have a train that gets in before 6 a.m. because it’s something we’ve talked about for years,” said Manager of Service Design Dan Miodonski. “We wanted to see if there was a market out there for people who have 6 a.m. starts at their jobs.”

In addition to equipment needs, the team must also consider infrastructure limitations. When the UP North Line schedule changed in April 2018, it was because a major bridge replacement project was going to require periods where trains could operate on only one track. Metra schedulers had to move meets – the term for when two trains in opposite directions cross paths – farther north on the line because of the single track.

Connections to other modes of transit, interaction with freight railroads, maintaining the same level of service, ridership data, customer feedback and the impact changes could have on riders play major roles in the schedule design process. The service design team is also hyper aware of when trains arrive and leave downtown Chicago, knowing that commuters generally want about 20 minutes to get between their train and work.

The goal is to provide as much service as possible while working within limits, including lack of yard or track space to slot additional trains if the equipment was available, the need for diesel trains to be serviced midday and contractual agreements with freight railroads that restrict when and how many trains can run.

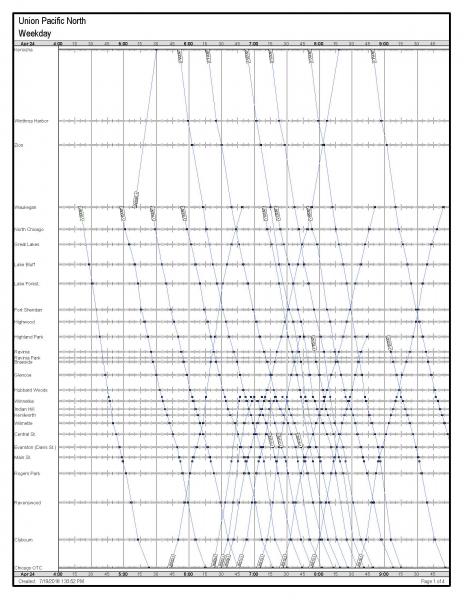

With a rough timetable in place, schedulers then use a tool that’s standard in the railroad and transit industry: a stringline. A stringline is a time and distance graph in which trains are represented by lines and their stops are represented by dots. (Before computers these diagrams were actually made up of strings pinned on bulletin boards).

“It gives you a much better idea of what’s happening in real time,” said Service and Schedule Design Specialist Trey Blaise. “Looking at the timetables is fine, but you’re only seeing one direction; you’re not seeing what the interaction actually is in specific places. It’s all visual right here. You can find issues much quicker than looking at times on a timetable.”

A stringline chart is the make or break point for schedules in the early stages. It can show that times need to be adjusted so opposing trains aren’t meeting at a station, or it can confirm that a schedule will work. With the newest BNSF schedule, the goal was to have at least four minutes between each train arriving at Chicago Union Station. The nearly equidistant lines curving to the top of the stringline chart illustrated that had been achieved.

From the outset, Metra’s schedulers work with the transportation managers for the respective lines, as well as Metra’s contract carriers, BNSF and Union Pacific. Their say and input weighs heavily on the schedule design process because they have insight that a train’s GPS data can’t show.

“Say the train always gets to a station at 6:41, and the engineer says ‘Yes, I get there at 6:41 because I’m going slow to meet the schedule. I could get there at 6:39 going track speed. Your schedule is too conservative.’ We wouldn’t know that, but the district would,” Miodonski said.

The next step is to present a proposed schedule to the public and gather feedback. All comments are documented and analyzed, and changes are made to the draft schedule. For instance on the Rock Island, the proposed schedule had originally included some earlier afternoon outbound trains based on the new early morning inbound train. However, customers resoundingly said they did not like the earlier outbound trains.

“You want to make sure you have a big picture of what’s your total objective in the schedule, but we will make adjustments if we see enough people commenting on one thing,” Miodonski said. “Even though it might make sense to us, we won’t make that change if it’s going to disrupt that many people and it’s not what they want.”

It takes about 40 days from the time the schedule is finalized until it is implemented. In that time, a number of tasks must be completed. To name a few: Metra updates train information accessed online and GPS data, prints schedules, assigns crews and alerts the media and public of the changes.

The work doesn’t end when the schedule is implemented. From there, Metra’s transportation team tracks the schedule’s performance by riding trains, reviewing customer feedback and counting passengers. One aspect of that is determining how well the forecast for which trains customers would gravitate to matches up with reality. It’s not an exact science, and sometimes predictions don’t line up with actual ridership, especially on a schedule as dense as the BNSF. But Metra has refined its forecasting in the past year based on current on/off counts, conductor counts, and, most recently, information from the customers themselves.

“For the Rock Island schedule, we asked people what train they would take based on the draft schedule as a way to forecast what trains riders would actually take and how light or heavy a train would be,” Blaise said.

Changes can be made to the schedule, though not immediately. In the case of the BNSF schedule, for instance, Metra and BNSF Railway in February asked for additional customer feedback in anticipation of making minor modifications to improve the schedule later this year.

The schedule design process will continue to be refined as Metra considers its role as part of a greater transit network serving the six-county region and adjusts to the demands of PTC and its customers.